Why the FBI Was Fascinated by the Artist Mark Lombardi

Hello and welcome to the November edition of the newsletter! I’m Arnav, an associate producer at Brazen. For the past few months, we’ve been working hard on a brand-new podcast series, and I’m excited to share it with you today. It’s about an artist named Mark Lombardi.

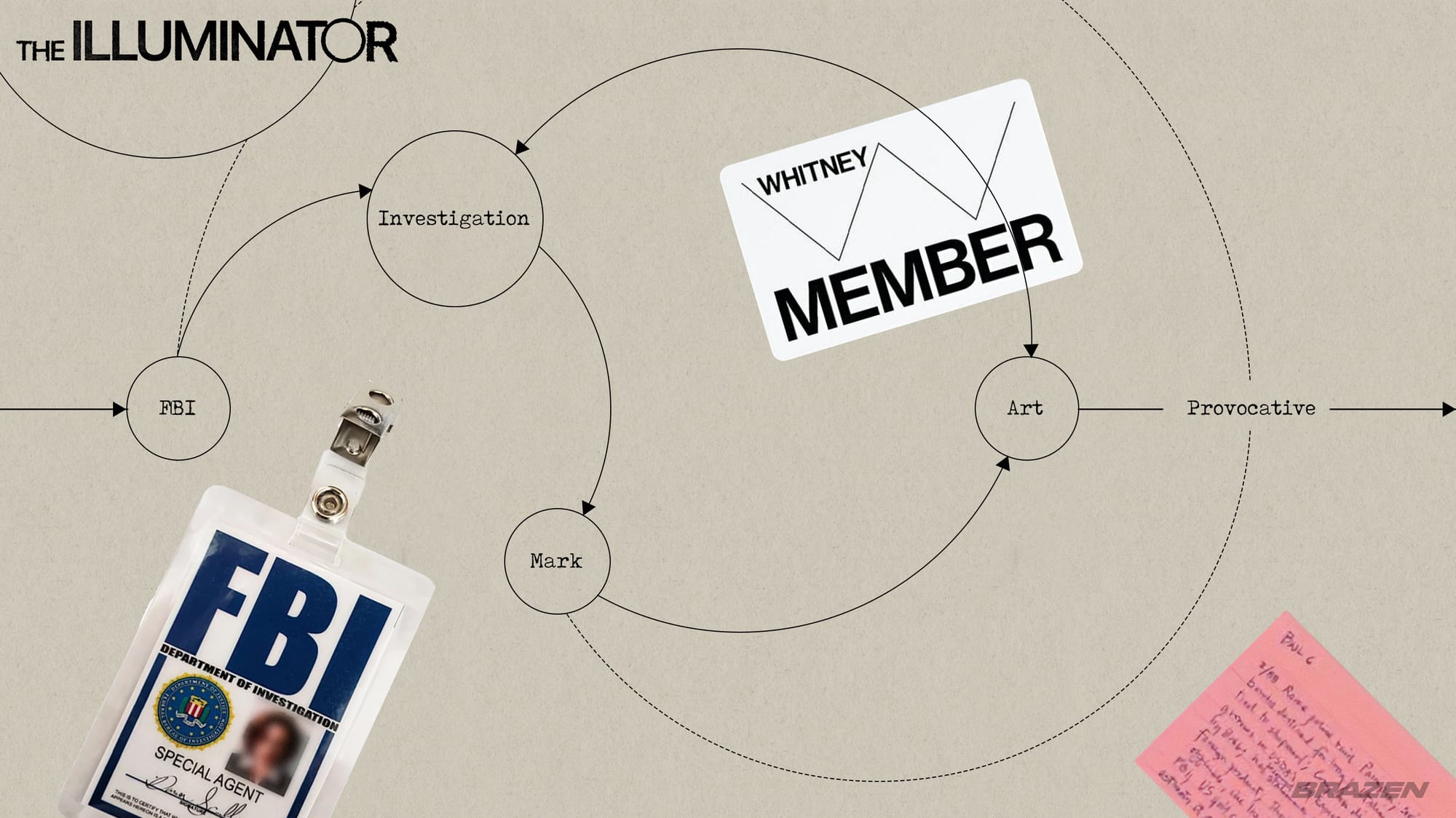

Mark carried business cards promising “death-defying acts of art and conspiracy.” It’s considered a wry joke — until he turns up dead. A conceptual artist, Mark’s vast drawings map financial networks linking the powerful and corrupt. So his sudden death, on the cusp of international recognition, leaves his friends and family with troubling questions. Was Mark's tragic end truly of his own making — or did he uncover something worth silencing?

Our new show about Mark’s life and work is out today. It’s titled The Illuminator: Art, Conspiracy and Madness, and it’s available wherever you listen to podcasts.

Mark’s most well-known piece — his magnum opus — was a vast drawing, more than 11 feet wide, about a bank you may not have heard of, but which was at the heart of a maze of conspiracies in the ’80s. It was called the Bank of Credit and Commerce International — founded by a Pakistani financier, registered in Luxembourg, with headquarters in London.

BCCI gave criminals, drug lords, and corrupt politicians unfettered access to the global financial system. The CIA allegedly used it as a backchannel method of sending millions of dollars in secret U.S. aid to Afghan mujahideen groups. Saddam Hussein and the Medellín Cartel reportedly used it to launder money. And all the while, the bank had connections to the highest levels of the U.S. government.

We discuss all of these connections and more in The Illuminator. Before you go listen, I also want to share with you an excerpt of a special interview with Lawrence Rinder, who curated an exhibition featuring Mark’s work at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, which purchased many of Mark’s BCCI drawings. Shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks, an FBI agent showed up at the Whitney, asking to view Mark’s BCCI drawing. Here’s Lawrence telling Farah Halime, Brazen’s head of creative, the full story.

Farah: I thought we'd start with this work of Mark Lombardi's, the big piece of work — the BCCI. Can you actually talk me through the piece itself and how you went about acquiring it?

Lawrence: This was the last major piece that Mark made before he died, and he finished it in 2000. I think he was working on it for about four years, from 1996 to 2000. It's an enormous piece. For people who know Claude Monet’s Water Lilies, or a Jackson Pollock drip painting — it has that kind of scale and presence.

I was very impressed with it and loved it, and recognized immediately that this was not only a great work of art, but the tip of an iceberg of kind of incredible and very unusual talent. And even though Mark, at that time, was not well-known, I thought it was important for the Whitney to take a chance and get this monumental piece — not just get a few small drawings or something, but really go for it

Farah: Can you tell me a little bit about how you felt when [the FBI] called the museum and your response?

Lawrence: Mark’s work documents these extensive networks — you could use the word “conspiracy,” I guess — related to finance, terrorism, politics. And the work involved a tremendous amount of research. The FBI did contact the museum in 2001. I believe some agents actually came to the museum. I was not there at the time. I came in, and I think one of my assistants said, “Oh, you missed the FBI. They were here.” It’s just not the sort of thing that happens every day. Why would the FBI want to look at a work of art in our collection? But you have to remember that this incident occurred within less than two months after the Sept. 11 attack on the World Trade Center.

Farah: What’s interesting about that particular work — and all of his works as taken together — is that he never concludes anything. He just merely displays them without any judgement. Why do think that the FBI was interested in a piece of work that seemed so elusive?

Lawrence: I think to the extent that they were interested in it, I would imagine it was because underlying his work, however elusive it might ultimately be, was a tremendous amount of actual research. He was a trained researcher and a trained archivist, and he knew how to do this work, which was in advance of the internet, or at least the internet as we know it. So it was really kind of hard slogging checking probably in archives, newspaper records. God knows how he did it, but he kept notes on file cards. It was really old-school sleuthing. And then he used that information to make art.

The FBI was probably grasping for straws — they were faced with the worst catastrophe to hit the mainland U.S. since, I don’t know, the war of 1812. I don’t think they were looking for his conclusions so much as maybe some random name that would show up there that they hadn’t thought of.

If you’d like to hear more from Lawrence, listen to the pre-bonus episode of The Illuminator for the rest of the interview.

The first episode of The Illuminator: Art, Conspiracy and Madness is available right now. New episodes come out each Monday (if you’d like to listen to them early, you can do so by subscribing to Brazen+ at brazen.fm/plus).